Discovery of Germs, Mothers Died of Baby Fever

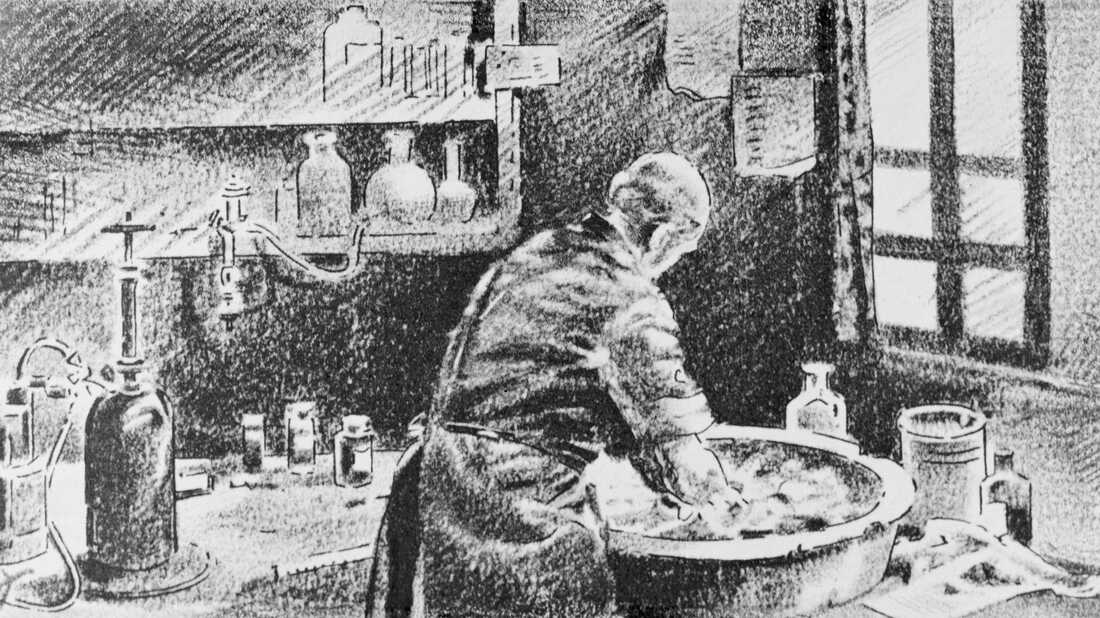

Ignaz Semmelweis washing his hands in chlorinated lime water before operating. Bettmann/Corbis hibernate caption

toggle explanation

Bettmann/Corbis

Ignaz Semmelweis washing his easily in chlorinated lime water earlier operating.

Bettmann/Corbis

This is the story of a human whose ideas could have saved a lot of lives and spared countless numbers of women and newborns' feverish and agonizing deaths.

Yous'll discover I said "could have."

The year was 1846, and our would-be hero was a Hungarian doctor named Ignaz Semmelweis.

Semmelweis was a human being of his time, according to Justin Lessler, an assistant professor at Johns Hopkins School of Public Health.

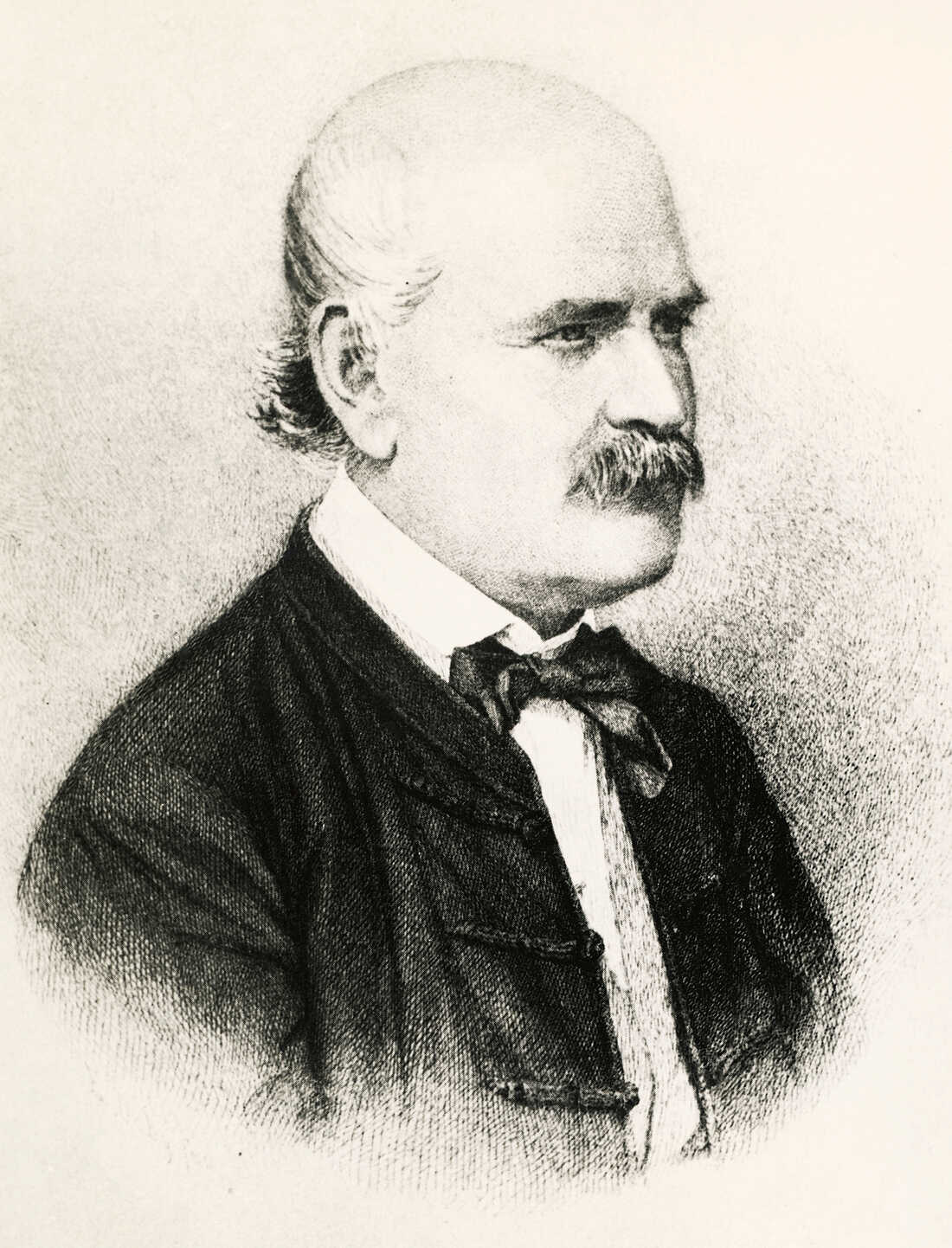

Semmelweis considered scientific inquiry part of his mission equally a dr.. De Agostini Moving-picture show Library/Getty Images hibernate caption

toggle explanation

De Agostini Picture Library/Getty Images

Semmelweis considered scientific inquiry part of his mission as a dr..

De Agostini Movie Library/Getty Images

It was a fourth dimension Lessler describes as "the start of the gilt age of the medico scientist," when physicians were expected to take scientific training.

So doctors like Semmelweis were no longer thinking of illness as an imbalance caused by bad air or evil spirits. They looked instead to anatomy. Autopsies became more common, and doctors got interested in numbers and collecting information.

The young Dr. Semmelweis was no exception. When he showed up for his new chore in the maternity dispensary at the General Hospital in Vienna, he started collecting some information of his own. Semmelweis wanted to figure out why and so many women in maternity wards were dying from puerperal fever — normally known every bit childbed fever.

He studied two motherhood wards in the hospital. One was staffed past all male person doctors and medical students, and the other was staffed by female person midwives. And he counted the number of deaths on each ward.

When Semmelweis crunched the numbers, he discovered that women in the dispensary staffed by doctors and medical students died at a charge per unit nearly v times higher than women in the midwives' clinic.

Just why?

At Vienna General Hospital, women were much more likely to die after childbirth if a male md attended, compared to a midwife. Josef and Peter Schafer/Wikipedia hide caption

toggle caption

Josef and Peter Schafer/Wikipedia

At Vienna Full general Hospital, women were much more than probable to die later on childbirth if a male person doc attended, compared to a midwife.

Josef and Peter Schafer/Wikipedia

Semmelweis went through the differences between the two wards and started ruling out ideas.

Right abroad he discovered a big difference betwixt the two clinics.

In the midwives' clinic, women gave birth on their sides. In the doctors' dispensary, women gave birth on their backs. So he had women in the doctors' clinic requite nativity on their sides. The outcome, Lessler says, was "no effect."

Then Semmelweis noticed that whenever someone on the ward died of childbed fever, a priest would walk slowly through the doctors' clinic, past the women's beds with an attendant ringing a bell. This time Semmelweis theorized that the priest and the bong ringing so terrified the women afterwards birth that they developed a fever, got ill and died.

So Semmelweis had the priest modify his route and ditch the bell. Lessler says, "It had no effect."

By now, Semmelweis was frustrated. He took a go out from his hospital duties and traveled to Venice. He hoped the break and a good dose of fine art would clear his caput.

When Semmelweis got back to the hospital, some distressing just important news was waiting for him. Ane of his colleagues, a pathologist, had fallen ill and died. It was a common occurrence, co-ordinate to Jacalyn Duffin, who teaches the history of medicine at Queen'south University in Kingston, Ontario.

"This frequently happened to the pathologists," Duffin says. "There was nothing new virtually the way he died. He pricked his finger while doing an autopsy on someone who had died from childbed fever." And then he got very sick himself and died.

Semmelweis studied the pathologist'southward symptoms and realized the pathologist died from the same thing every bit the women he had autopsied. This was a revelation: Childbed fever wasn't something only women in childbirth got sick from. It was something other people in the hospital could get sick from as well.

But it nonetheless didn't reply Semmelweis' original question: "Why were more women dying from childbed fever in the doctors' dispensary than in the midwives' clinic?"

Duffin says the death of the pathologist offered him a clue.

"The big difference between the doctors' ward and the midwives' ward is that the doctors were doing autopsies and the midwives weren't," she says.

So Semmelweis hypothesized that there were cadaverous particles, picayune pieces of corpse, that students were getting on their hands from the cadavers they dissected. And when they delivered the babies, these particles would go inside the women who would develop the illness and dice.

If Semmelweis' hypothesis was right, getting rid of those cadaverous particles should cut downward on the death charge per unit from childbed fever.

So he ordered his medical staff to start cleaning their easily and instruments not merely with soap but with a chlorine solution. Chlorine, as we know today, is well-nigh the best disinfectant at that place is. Semmelweis didn't know anything about germs. He chose the chlorine because he thought it would be the best way to become rid of any smell left backside by those footling bits of corpse.

And when he imposed this, the rate of childbed fever savage dramatically.

What Semmelweis had discovered is something that still holds true today: Hand-washing is one of the most important tools in public health. It tin can keep kids from getting the flu, preclude the spread of disease and keep infections at bay.

Yous'd call up everyone would be thrilled. Semmelweis had solved the problem! Only they weren't thrilled.

For i thing, doctors were upset because Semmelweis' hypothesis made information technology look like they were the ones giving childbed fever to the women.

And Semmelweis was non very tactful. He publicly berated people who disagreed with him and made some influential enemies.

Eventually the doctors gave upwards the chlorine hand-washing, and Semmelweis — he lost his job.

Semmelweis kept trying to convince doctors in other parts of Europe to wash with chlorine, but no one would heed to him.

Even today, convincing health care providers to take mitt-washing seriously is a challenge. Hundreds of thousands of hospital patients get infections each year, infections that tin can be deadly and hard to treat. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says manus hygiene is one of the virtually of import ways to prevent these infections.

Over the years, Semmelweis got angrier and somewhen even strange. In that location's been speculation he adult a mental status brought on by mayhap syphilis or even Alzheimer's. And in 1865, when he was only 47 years sometime, Ignaz Semmelweis was committed to a mental asylum.

The pitiful end to the story is that Semmelweis was probably browbeaten in the asylum and eventually died of sepsis, a potentially fatal complication of an infection in the bloodstream — basically, it'southward the aforementioned disease Semmelweis fought so hard to preclude in those women who died from childbed fever.

Source: https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2015/01/12/375663920/the-doctor-who-championed-hand-washing-and-saved-women-s-lives

Post a Comment for "Discovery of Germs, Mothers Died of Baby Fever"